When Nick admires Juliet’s looks or is baffled by her occasionally nonsensical remarks he is speaking for the audience. Like Juliet he is a mish-mash of object/subject - a character who serves the story and dialogue while also acting as the digital personification of the straight male player. The presence of her boyfriend Nick - a very much alive but decapitated head hanging from Juliet’s belt - acts as a kind of governing force over the whole thing.

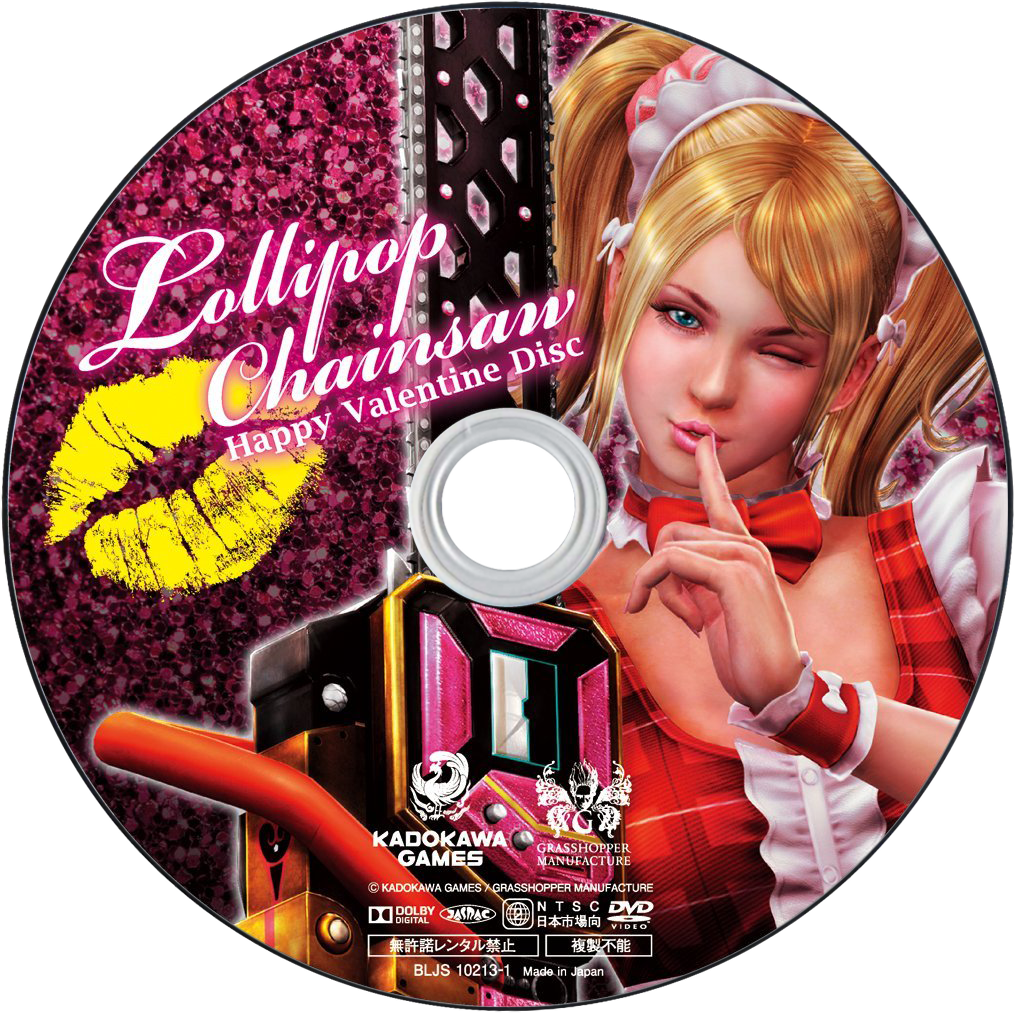

#Lollipop chainsaw x male reader skin

Instead, we’re meant to live in her skin for a bit and reflect a bit more deeply on why it is that she, a character who looks like the current Western Platonic ideal of a young woman, is still so insecure about the size of her butt. Juliet is written as a vapid sex object, but players are not allowed to be removed from her. The effect of playing as, rather than just watching, this character forces the audience to take on some aspect of her identity. Juliet is, essentially, Chainsaw’s way of putting players into the shoes of the same masturbatory fantasy that the generic (straight, adolescent-minded male) audience of videogames are usually asked to blindly objectify rather than relate to. The uncomfortable voyeurism of the game’s introduction never goes completely away (there is a frightening achievement/trophy that encourages peeping up Juliet’s skirt for example), but Lollipop Chainsaw saves itself by ultimately forcing the question of who - the game or the player - is passively denigrating whom. Surprisingly, after a few hours of play this type of creepiness has begun to subside, gradually becoming diluted by a stronger current of winking, seemingly self-aware, humour.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)